Bread baking and writing go "hand in hand." What I learn from one, I gain in the other. Using my past experience of creating beautiful, delicious, yet healthful and uncompromised breads, I now set to the task of writing my first book. I say, "If I could make whole wheat rise . . . "

Thursday, December 19, 2013

Breakfast at Fontecruz, Lisboa

Puny silver-haired Frenchman and

his underage Anthropologie-clad

mistress -- all her decades of lace and old-fashioned

frill, his brown checkered pants

cinched at the waist

by a belt pulled too tight, complaining

in high-pitched French tones, there's no

eggs at the buffet! then

smiling beside himself at her

seated glance of approval while

the Lisboan scrambles

for his, the sound of one, two, three wet

smooch, making himself

an escargot of it all.

Sunday, November 24, 2013

Walking into Walls

Strolling along the beautiful patterned walkways of Lisbon, one eventually comes to a wall -- that is, tile walls -- for which the Portuguese are known worldwide.

Tile making, or azulejos, probably comes from the Arabic word azure which means 'smooth surface.' It's hard to put a date on when the Portuguese became the most renowned tile makers in the world because azulejos came to Portugal via Moorish influence (dominance) well over 1,000 years ago -- and Spanish influence (dominance) about 500 years ago.

Both cultures contributed a diverse style of tile making, which was really, in its primitive state, just "wall making" -- designed to keep out rebellious subjects. I stood for a long time at this crude Moorish wall that surrounds what is now called St. George's Castle, built on the highest peak in Lisbon by the conquering Moors around 800 A.D. Today it is a popular lookout post for lackadaisical peacocks. Some areas of the fortress date to the 4th century.

Moorish design is characterized by geometrical patterns and extensive symmetry. Early examples were devoid of color because the technique for using color was not devised until the late 1500s.

The technique for color, called maiolica, came to Portugal through Spain -- and to Spain through Mesopotamia in the 9th century -- and to Mesopotamia from China. Color led to an outpouring of patterns and creativity . . .

Blue and white is considered to come from the influence of Chinese ceramics, brought back to Portugal through India after Vasco da Gama famously discovered the trade route to India and Asia in the late 1400s.

The most humble of restaurants and pastry shops is graced with tile wall patterns, both inside and outside. This is the exterior wall of a tiny restaurant called "Istanbul Pizza Shop."

This exterior wall graces one restaurant on a tiny island in the Tagus River, the longest river on the Iberian Peninsula. It runs east to west through Spain, and empties into the Atlantic Ocean off the coast of Lisbon. As we sat outside and ate salted dried codfish and drank vinho verde wine, I wondered what significance those petite floral patterns held -- because, as I came to learn, virtually everything in Portugal carries symbolic significance. The interior walls were just as beautiful as the exterior.

No place shows the diverse styles of tile making more than at Pena Palace, which is located about 45 miles from Lisbon. This was the summer palace for the Royal Court through 1,000 years of history and changing regimes -- beginning of course with the Moors in medieval times, and ending with the rein of Don Manuel II in 1910. Each regime, or conquerer, preserved the existing artistry of the palace, but added its own "updated" style -- therefore it is a panoply of architectural and tile making history.

Legend is just as important (and real) to the Portuguese as documented history. We were told by a native Lisboan that "if it happened in Portugal, there is a legend for it." And if there is a legend for it, she added, there is probably something built to commemorate it . . . to honor it . . .

Tile making is one very useful mode of expression to catalogue the nation's identity. Symbolic representations of the country's folklore, legends, heroes, and history are literally spread out on the walls for citizens to absorb daily. Perhaps history books for young children are optional!

I was strangely drawn to a circular pattern with a knot in the center, which I later learned is called arbiter esfera, or the armillary sphere. It is a symbol of the constellations, but representative of the nation's great seafaring history. In its glory days, beginning in the late 1400s when Vasco da Gama discovered the trade route to India, Portugal dominated the Indian Ocean and therefore economic trade for well over a century.

I could not bring home a wall of tiles, or even take pictures of all the walls I loved, but I settled for three beautiful tiles which caught my eye (and would not let me go home without them). I found them in an antique store just down the steep hill from the old Moorish castle that overlooks modern day Lisbon. They date to 1750, which means they were crafted before the catastrophic 9.0 earthquake of 1755 which devastated the nation and left it in ruins for nearly a century.

The antique dealer from whom I bought these tiles noted that he had never seen a pattern such as the third one shows -- "not even in tile museums," he said. As I contemplate that third tile from my seat at the kitchen table at home, I surmise that it may have been the singular experiment of a woman who was not really a tile maker by trade -- perhaps her husband or father or brother was a tile maker -- and perhaps she had an idea for a trellis type design which she had got from observing the way vines grow along a fence outside her kitchen window or along the tiled walkway on her way to market -- and maybe her father or brother or husband said it was not such a good design because it had never been done before -- and so she stopped making tiles after that first one -- but somehow this tile survived the catastrophic earthquake of 1755 -- though maybe she did not -- and maybe she had a bit of Moorish or Arabic blood in her from long ago -- because, when I sit back and look at this tile long enough, those vines begin to look like Arabic writing . . .

Tile making, or azulejos, probably comes from the Arabic word azure which means 'smooth surface.' It's hard to put a date on when the Portuguese became the most renowned tile makers in the world because azulejos came to Portugal via Moorish influence (dominance) well over 1,000 years ago -- and Spanish influence (dominance) about 500 years ago.

Both cultures contributed a diverse style of tile making, which was really, in its primitive state, just "wall making" -- designed to keep out rebellious subjects. I stood for a long time at this crude Moorish wall that surrounds what is now called St. George's Castle, built on the highest peak in Lisbon by the conquering Moors around 800 A.D. Today it is a popular lookout post for lackadaisical peacocks. Some areas of the fortress date to the 4th century.

The technique for color, called maiolica, came to Portugal through Spain -- and to Spain through Mesopotamia in the 9th century -- and to Mesopotamia from China. Color led to an outpouring of patterns and creativity . . .

The most humble of restaurants and pastry shops is graced with tile wall patterns, both inside and outside. This is the exterior wall of a tiny restaurant called "Istanbul Pizza Shop."

This exterior wall graces one restaurant on a tiny island in the Tagus River, the longest river on the Iberian Peninsula. It runs east to west through Spain, and empties into the Atlantic Ocean off the coast of Lisbon. As we sat outside and ate salted dried codfish and drank vinho verde wine, I wondered what significance those petite floral patterns held -- because, as I came to learn, virtually everything in Portugal carries symbolic significance. The interior walls were just as beautiful as the exterior.

No place shows the diverse styles of tile making more than at Pena Palace, which is located about 45 miles from Lisbon. This was the summer palace for the Royal Court through 1,000 years of history and changing regimes -- beginning of course with the Moors in medieval times, and ending with the rein of Don Manuel II in 1910. Each regime, or conquerer, preserved the existing artistry of the palace, but added its own "updated" style -- therefore it is a panoply of architectural and tile making history.

Legend is just as important (and real) to the Portuguese as documented history. We were told by a native Lisboan that "if it happened in Portugal, there is a legend for it." And if there is a legend for it, she added, there is probably something built to commemorate it . . . to honor it . . .

Tile making is one very useful mode of expression to catalogue the nation's identity. Symbolic representations of the country's folklore, legends, heroes, and history are literally spread out on the walls for citizens to absorb daily. Perhaps history books for young children are optional!

I was strangely drawn to a circular pattern with a knot in the center, which I later learned is called arbiter esfera, or the armillary sphere. It is a symbol of the constellations, but representative of the nation's great seafaring history. In its glory days, beginning in the late 1400s when Vasco da Gama discovered the trade route to India, Portugal dominated the Indian Ocean and therefore economic trade for well over a century.

The antique dealer from whom I bought these tiles noted that he had never seen a pattern such as the third one shows -- "not even in tile museums," he said. As I contemplate that third tile from my seat at the kitchen table at home, I surmise that it may have been the singular experiment of a woman who was not really a tile maker by trade -- perhaps her husband or father or brother was a tile maker -- and perhaps she had an idea for a trellis type design which she had got from observing the way vines grow along a fence outside her kitchen window or along the tiled walkway on her way to market -- and maybe her father or brother or husband said it was not such a good design because it had never been done before -- and so she stopped making tiles after that first one -- but somehow this tile survived the catastrophic earthquake of 1755 -- though maybe she did not -- and maybe she had a bit of Moorish or Arabic blood in her from long ago -- because, when I sit back and look at this tile long enough, those vines begin to look like Arabic writing . . .

Wednesday, October 30, 2013

Walkabout Lisbon

The sidewalks -- that is the first thing I noticed when I stepped out of the hotel lobby onto Avenida Liberdade in Lisbon, Portugal -- the beautiful mosaic patterned sidewalks. On that first day of walking through Lisbon I think I did not even lift my eyes to look at the numerous monuments and cathedrals, Moorish castles, or perpetual blue skies that graced our weeklong visit -- because the limestone sidewalks were so beautiful. And the more we walked, the more varied and interesting the sidewalks became . . .

Most of the city's sidewalks were made by prisoners in the early 1800s. It was thought that the prisoners needed something to do with their time, and that the "something" ought to benefit the nation. Therefore, they were put to work creating much-needed walkways for a city that had been devastated nearly to extinction by a 9.0 earthquake and tsunami on November 1, 1755. It is a day still talked about by Lisboans -- their history, their art, and even items for sale in antique stores, are categorized as "before the earthquake" or "after the earthquake." I bought three beautiful tiles from "before the earthquake," that is, from 1750 -- "survivors," the store owner called them.

The Marquis of Pombal, the Secretary of State during the reign of Joseph I in the late 18th century, is much honored and credited with foreseeing the benefit of a "grid pattern" in rebuilding Lisbon after the earthquake. Nothing was left to the city but rubble and mud at that time, and so anything could have replaced it. The previous layout of Lisbon, like all medieval cities, had been designed on a circular pattern in which the city radiated out from a commercial "center" (from which our word city is derived).

At the time, The Marquis was criticized (or at least questioned) for making the sidewalks so wide. His response was, they may seem wide now, but someday they will be filled with people. Many monuments exist throughout the city to pay homage to this man with such foresight, but I admit I did not take a single picture of his monuments -- simply because I was taken up by the handiwork of his position, not by the man himself. Is this not the mark of a true leader?

The "Alfama" district of Lisbon was miraculously saved from total destruction during the 1755 earthquake. Therefore, the medieval winding walkways still exist. This is an area built primarily by the dreaded and overbearing Moors of the 9th and 10th centuries. History is filled with accounts of Portuguese struggles (battles/wars) to overcome Moorish rule. However, hated as the Moors were, their buildings -- and walkways -- were indestructible. These 1,000-plus-year-old walkways are still trodden by the likes of me today. One can spend a pleasant day tangled up in Alfama's winding streets while looking for Fado houses or family restaurants serving inexpensive lunchtime fare of salted dried codfish and local olives and pitchers of delicious Vinho Verde. I will always remember those meals -- and those inclusive pitchers of wine -- and the winding narrow walkways that would miraculously lead us out of Alfama and onto the familiar grid-like streets.

The walkways are made from a type of limestone, called "creme lioz," that is abundant in the nation. Each small tile, as they are called, is chiseled by hand and made to fit into the ground about two or three inches deep; it is made smooth on top, and placed into patterns like puzzle pieces. The tiles come primarily in two natural colors -- black and white -- though I have noticed (in the proximity of monasteries or cathedrals, at least) there is also a natural pink and a brownish-bronze.

I think one of the most profound traits of the Portuguese people is their natural inclination to give thanks. I noticed that people often greet each other by saying, Obrigado, or thankyou! They are thankful for the many miracles on which their country's legends are based, for their rich history, for overcoming Moorish dominance, for strong family ties, for the bounty of fish which the Atlantic Ocean provides, and for the beauty all around them.

Even the dogs seem to pay homage to the city's sidewalks by mimicking its native colors. I call this photo "Black and White." Only seconds after this photo was taken, the cute pup ventured to attack a white pit bull (unleashed) as it strolled by.

In a country deemed by economists to be one of the poorest in Europe, where unemployment staggers at 30 per cent, and where many educated men and women sleep on the sidewalks which I've shown -- there is art everywhere. One young woman, Margarida, who works three jobs to make ends meet (one of which is to conduct weekend walking tours for English speaking tourists), said, "I wish I could be a tourist in my own city. It is hard to make a living here, but it is beautiful!"

Thursday, October 24, 2013

Holy Water Fonts of Portugal

Friday, June 14, 2013

Gregory's Pond

|

| A short pathway to the lake . . . |

Greg – the neighborhood

nature photographer who died of pancreatic cancer a few months ago. I only know he died because I saw his

obituary in the newspaper. Greg lived

about two blocks up the street, and I never knew his last name or his wife’s

name, though I saw him often over the course of many years when I walked around the lake and he stood or sauntered

around the lake -- his head up in the trees or down to the ground, much equipment

always around his neck or crosswise on his chest. We talked briefly about what he had seen each

time we passed, and many years of brief talking had added up to what I call friendship.

|

| . . . quietly teeming with wildlife |

|

| The Blue Heron is patient with the amateur photographer . . . |

And on this short walk leading to the lake, I thought of

Greg to whom I would have reported my finding when I saw him next – or who

would have beat me to it and said, “Yes, I know, I saw them too – I got the

shot!” By shot, of course, he meant the

picture. He would have known the secret

of quietly waiting on a bench or standing still – to get some wondrous close-up shot that would possibly be on the front cover of Virginia Wildlife

magazine. His “amateur” photos made

several covers of this and other magazines, he had told me. He could somehow make his lens zoom right up

to a tree, if not miraculously behind the tree, to get a snapshot of a thing you

could never see while just looking – you

can never get that close in real life – and of course the object always darts

away before you can be sure of what you’ve seen – and you can’t preserve the

thing at all except by insisting on what you saw in memory alone – and memory is

always changing . . . at least that is my experience.

|

| There were six right before I snapped the shot |

The last time I talked to Greg's wife, and that was

during one of his several declines about a year ago, she said that Greg always

joked that the lake was named after him.

Everyone in the neighborhood refers to the lake as “Raintree Lake,” for

it is located right off Raintree Drive – but old county records or surveys,

Greg found out, refer to it as “Gregory's Pond.”

And so, she joked, “Greg considers this to be his pond.”

|

| I've seen turtles snatch goslings from beneath |

|

Saturday, May 25, 2013

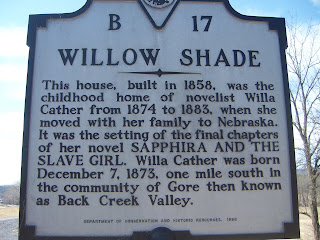

Willa Cather at Home

|

| Great American author, Willa Cather |

“The great disadvantage about writing of the places you love

is that you lose your beloved places forever – that is, if you are a quiet

person who doesn’t like publicity.” She wrote this in a letter to woman named

Miss Masterton, who had written Cather a ‘fan letter’ praising the latest novel

about a jealous landowner named Sapphira and a beautiful slave girl named

Nancy. (This quiet and very private person’s letters have been

published expressly against her wishes in a book called “The Selected Letters

of Willa Cather.” The editors state that

the “statute of limitations” has expired and that she is now part of our

cultural history.) Cather continues in

the same letter:

“I have not been back to Virginia since Sapphira was published . . . Such simple, honest, earnest people

live there. It would have been the same

forever if motor cars had never been invented . . . It was the most beautiful

piece of country road that I have ever found anywhere in the world. I never found anything in the Swiss or Italian

Alps so beautiful as that road once was.”

Apparently, Miss Masterton had taken a visit to Virginia to

trace the steps outlined in the novel.

“I seem fated to send people on journeys,” she remarks to Miss

Masterton, and then proceeds to tell her about other readers who have similarly

gone “a-journeying” to such places as Quebec and New Mexico, based on her

books. She tells her that the slave

girl, Nancy, is a real person, and that the story is based on an event that

actually happened. “She was exactly like

that, and old Till was just like that. I

was between five and six years old . . . “ – but Cather seems apologetic in the

letter when she refers to the house called “Willow Shade” where she lived from

ages 2 to 9:

|

| Cather's home from ages 2 to 9 |

“I am sorry you saw that desolate ruin which forty years ago

was such a beautiful place, with its six great willow trees, beautiful lawn,

and the full running creek with its rustic bridge. It was turned into a tenement house long

since, and five years ago the very sight of it made me shiver. Of course, it still lives in my mind, just as

that March day when Nancy came back still lives in my mind.”

Cather would perhaps be happy to know that Willow Shade, 70

years hence, is privately owned by a non-Cather family who reside there and

have restored it to historic standards – (though she was not to know that the house

served as a hospital for a short while after it was a tenement house).

|

| Willa Cather's birth home today |

The decrepit condition of her birth home would undoubtedly

cause Willa Cather to shiver profusely. She

most likely stayed in this home whenever she came to visit Virginia, for it was

owned at the time by Cather relatives.

In this home, in the years preceding the writing of Sapphira, I imagine she acquired both the inspiration and material for

her final novel. She made no comment

about this house in any of her letters that I have read so far, most probably

because it was well tended at the time and she had no concern or need to make

comment.

The home today is taken over by termites and neglect. Once lived in by Cather relatives, the home

has been abandoned for decades and is for sale by the current owner who would love

to see it preserved but does not have the resources or ability to do so

himself. Unfortunately, neither the State

of Virginia nor the literary scholars of our nation, nor the Willa Cather

Foundation of Red Cloud, Nebraska has shown any interest in preserving this historic

landmark – though a very nice sign in the front yard proclaims it a noteworthy

spot. And so, I stop by the house each spring

to linger and wonder, take a few pictures of the changes I see, and then leave.

While scholars busy themselves to publish private letters

that the author had expressly stated should never be published, the author’s own birth home – located near “the most beautiful piece of country road . . . in the world,” amongst a people

she said were the most honest and earnest

– is sadly given over to termites and the next big storm that deems to take

it down. We should all shiver to know

this.

|

| I imagine Willa Cather taking her first steps here |

|

| Did she gaze out this window while imagining Sapphira? |

Saturday, May 11, 2013

The Interrupting Cow

My eldest adult daughter, when she was

a young child, told a particular joke with such proficiency – never failing to elicit

the hoped-for surprise response from aunts, uncles, parents, and others – that

it endured for bounteous years. It was

one of the endless variations on the knock-knock series . . .

Who’s there?

Interrupting cow.

Interrupting cow wh . . .

Pause to explain.

This is where the child’s skill of ‘timing’ comes in, for she must

scream MOOOOOOO!!! in an obnoxious manner before the adult has had a chance to

finish the final response, “Interrupting cow wh . . .”

MOOOOOO!!!! Much

laughter ensues when the adult comes to realize what has just happened. The adult has been interrupted . . . MOOOOOOO!!!

This might define many years of motherhood for me . . .

I had a vision . . . I could see and feel and hear the

thoughts in my brain, perhaps manifested as brain synapses – tiny strands of matter

that connect and make sense of all the data coming and going -- and these connecting

synapses were being chopped into bits and pieces by a fine sewing scissors – all

day long. Perhaps the living links carried

thoughts or story ideas or plans for a future life, or the line of a poem I’d

write one day, or maybe just dialogue with myself – but interrupted, snip-snapped, all day long – until my

brain felt inside like a bowl of chopped up, one-half-inch sized spaghetti

pieces. This was my vision. And each night, as I slept, some of those

pieces (I could sense it, I say!) would secretly reconnect – and I would

remember . . . but then, a new day began and they would be disconnected, snip-snapped, again.

I often wondered what I was doing to my brain, what was

happening to my brain in those many years.

What would be the long-term accumulation, I asked, of always having the

brain synapses snipped just as they were trying to connect? Would there be a learned response for

disconnection? . . . would learning stop?

Would I develop an induced form of Attention Deficit Disorder? Would my brain eventually stop thinking

altogether? Was I creating Alzheimer’s

in myself? All those uncontrollable interruptions of young motherhood were coming at me from every angle . . . I felt them in the brain, saw the break, experienced

it, heard the sharp snip-snap, and I

worried about it. I often said, “I just

want to complete one sentence in my brain . . . without interruption.” I wanted to write books full of sentences

someday. What was to become of me?

|

| Brain synapse, "the connector" |

My fear – or hunch – has been corroborated. In the New York Times last Sunday I read an

article called “Brain, Interrupted” which studied, not mothers, but regular people, subjecting them to interruptions (only two! what a joke) while requiring them to perform a simple task of

reading something and answering questions about it. The Interrupted Group scored 20 percent lower

than the Control Group. “In other

words, the distraction of an interruption, combined with the brain drain of

preparing for that interruption, made our test takers 20 percent dumber,” the

article says.

The High Alert Group was warned there might be an

interruption, but the interruption never came.

Unbelievably, this group improved by 43 percent over the Control

Group. This surprise finding suggests

that participants learned from their experience, and their brains adapted. “Somehow, it seems, they marshaled extra

brain power to steel themselves against interruption, or perhaps the potential

for interruptions served as a kind of deadline that helped them focus even

better.”

Nowhere in the article does it mention snip-snapped synapses

or spaghetti bowl brains – but I had the vision (for I am prone to such things), and I know this is what happens.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)