|

| Great American author, Willa Cather |

“The great disadvantage about writing of the places you love

is that you lose your beloved places forever – that is, if you are a quiet

person who doesn’t like publicity.” She wrote this in a letter to woman named

Miss Masterton, who had written Cather a ‘fan letter’ praising the latest novel

about a jealous landowner named Sapphira and a beautiful slave girl named

Nancy. (This quiet and very private person’s letters have been

published expressly against her wishes in a book called “The Selected Letters

of Willa Cather.” The editors state that

the “statute of limitations” has expired and that she is now part of our

cultural history.) Cather continues in

the same letter:

“I have not been back to Virginia since Sapphira was published . . . Such simple, honest, earnest people

live there. It would have been the same

forever if motor cars had never been invented . . . It was the most beautiful

piece of country road that I have ever found anywhere in the world. I never found anything in the Swiss or Italian

Alps so beautiful as that road once was.”

Apparently, Miss Masterton had taken a visit to Virginia to

trace the steps outlined in the novel.

“I seem fated to send people on journeys,” she remarks to Miss

Masterton, and then proceeds to tell her about other readers who have similarly

gone “a-journeying” to such places as Quebec and New Mexico, based on her

books. She tells her that the slave

girl, Nancy, is a real person, and that the story is based on an event that

actually happened. “She was exactly like

that, and old Till was just like that. I

was between five and six years old . . . “ – but Cather seems apologetic in the

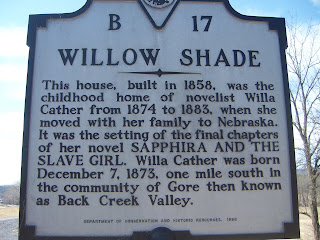

letter when she refers to the house called “Willow Shade” where she lived from

ages 2 to 9:

|

| Cather's home from ages 2 to 9 |

“I am sorry you saw that desolate ruin which forty years ago

was such a beautiful place, with its six great willow trees, beautiful lawn,

and the full running creek with its rustic bridge. It was turned into a tenement house long

since, and five years ago the very sight of it made me shiver. Of course, it still lives in my mind, just as

that March day when Nancy came back still lives in my mind.”

Cather would perhaps be happy to know that Willow Shade, 70

years hence, is privately owned by a non-Cather family who reside there and

have restored it to historic standards – (though she was not to know that the house

served as a hospital for a short while after it was a tenement house).

|

| Willa Cather's birth home today |

The decrepit condition of her birth home would undoubtedly

cause Willa Cather to shiver profusely. She

most likely stayed in this home whenever she came to visit Virginia, for it was

owned at the time by Cather relatives.

In this home, in the years preceding the writing of Sapphira, I imagine she acquired both the inspiration and material for

her final novel. She made no comment

about this house in any of her letters that I have read so far, most probably

because it was well tended at the time and she had no concern or need to make

comment.

The home today is taken over by termites and neglect. Once lived in by Cather relatives, the home

has been abandoned for decades and is for sale by the current owner who would love

to see it preserved but does not have the resources or ability to do so

himself. Unfortunately, neither the State

of Virginia nor the literary scholars of our nation, nor the Willa Cather

Foundation of Red Cloud, Nebraska has shown any interest in preserving this historic

landmark – though a very nice sign in the front yard proclaims it a noteworthy

spot. And so, I stop by the house each spring

to linger and wonder, take a few pictures of the changes I see, and then leave.

While scholars busy themselves to publish private letters

that the author had expressly stated should never be published, the author’s own birth home – located near “the most beautiful piece of country road . . . in the world,” amongst a people

she said were the most honest and earnest

– is sadly given over to termites and the next big storm that deems to take

it down. We should all shiver to know

this.

|

| I imagine Willa Cather taking her first steps here |

|

| Did she gaze out this window while imagining Sapphira? |